Copyright 2022, Ray Bonneville

I worked as a bush pilot in the Canadian wilderness for two seasons in 1989 and 1990...

KILLING FOG

The heading indicator swings wild in the panel as I desperately try to fight my way through and around the blinding cloud cover that has suddenly dropped down from above as I climbed out of the shallow river basin. I know right off that I’ve made a deadly mistake. The back of my throat is suddenly filled with the acidic taste of fear, reminiscent of the incoming rocket and mortar fire I had lived through in Dong Ha, Vietnam in 1968.

The kid is looking around trying to get a read on me and the tense situation. I’m too busy keeping us in the air at a hundred plus miles an hour a few feet off the treetops to even look at him. I’m struggling to find my calm, to control the panic flooding my blood. At this point I’m just trying to stay airborne. We are going whichever way the limited visibility will allow, regardless of the heading I need to be on to get down to Clova. I am burning too much fuel trying to settle down and get oriented. Torn, disheveled rags of fog hang down into the pines in wispy shreds. If I fail to keep the ground in sight, the kid and I are dead.

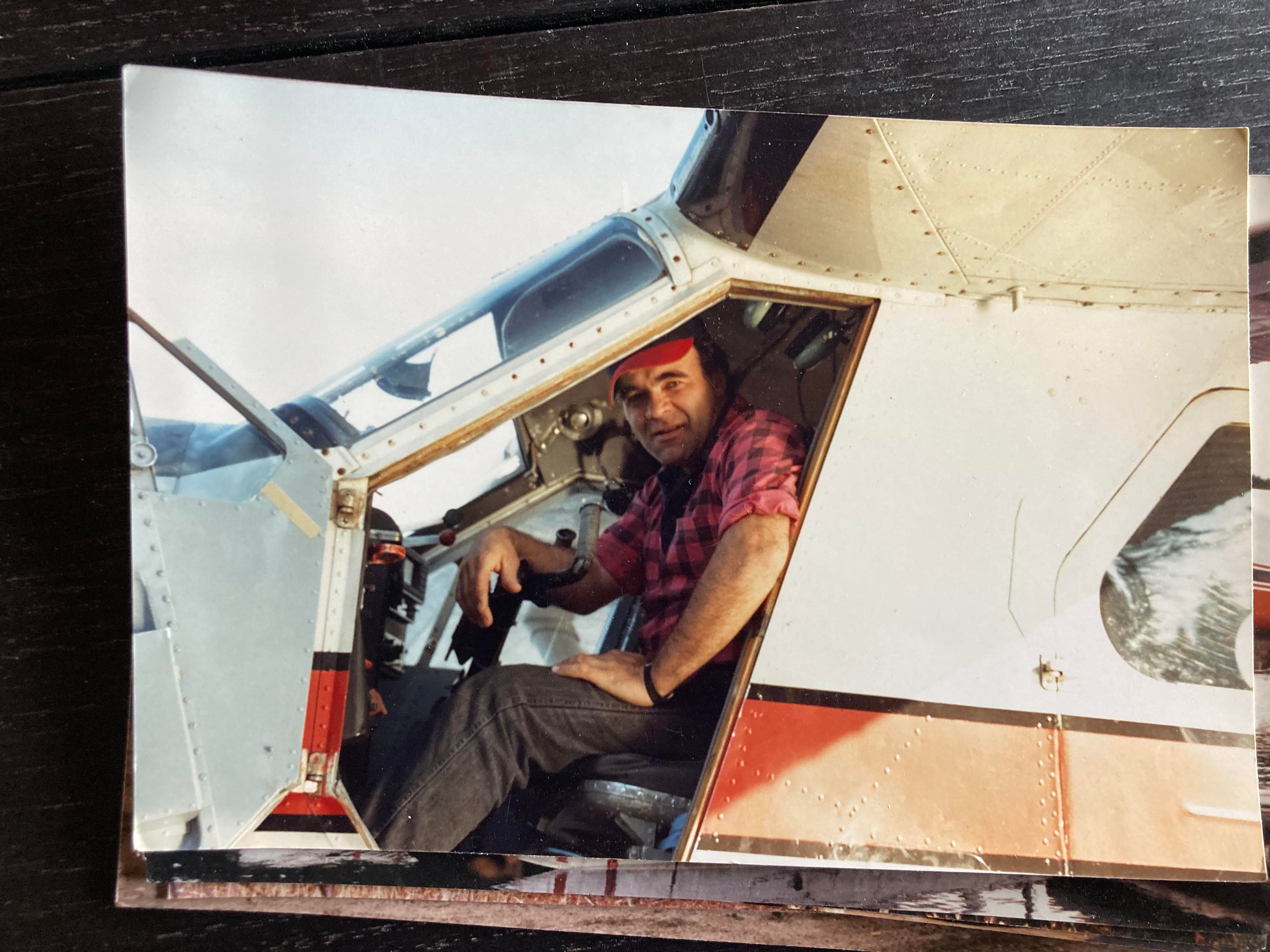

The day had started like a lot of days during the fall moose-hunting season in the Quebec bush. Under a low grey cloud ceiling, I followed the early morning ritual of pumping out the floats, fueling the plane, checking the oil level and cleaning the windshield. Evelyn was on the dock and pointed out my destination on the map. I pushed the plane away from the dock, worked the hand fuel primer and hit the starter switch until the nine-cylinder motor caught. I loved the uneven rumbling sound the four hundred fifty horsepower motor made, and the heady smell of motor oil in the cockpit.

The first mistake I made was allowing it to slip my mind that a week before I had dropped off two other hunters in the region I was heading into that day. They were now socked in at a higher elevation, higher than the cloud cover had been for the last few days, and they were surely running low on supplies. I usually relied on Evelyn to remind me of such things, but she hadn’t mentioned it.

I had enough fuel on board to get to my destination and back, plus roughly an extra hour’s worth. Had I remembered the stranded hunters, I likely would have thought more carefully about it. Fuel is heavy, and the decision about how much to have on board depends on the weight you’ll be carrying, which was as yet unknown to me.

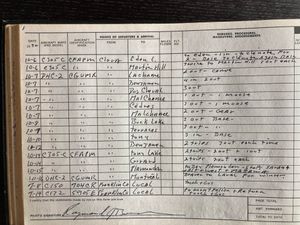

I taxied out onto the lake, jotting the date and time in my flight log. I did my run-up to check the mags and prop, then pumped down ten degrees of flaps. I pulled the water rudders up and poured on the power into the wind, holding the yoke all the way back into my chest to get the floats up and out of the water and gather enough speed to get airborne. They call it getting on “the step.”

Evelyn was running Air Tamarac by herself. A month earlier I’d flown her partner Jacques to get medical attention for his chest pains at the La Tuque hospital, and they’d kept him for open heart surgery. He would not be back this season. She usually stood on the dock watching the plane get smaller as it went. She’d listen for the drop in RPM that comes with every takeoff, and when she heard it, she would go back into the office, knowing I was up and on my way.

The air was smooth as a baby’s ass, like it often is under a low ceiling. A few seconds later I was headed northwest under a surly two-hundred-foot cloud cover. Scud-running under a low ceiling is the norm in bush flying. An hour earlier the cloud cover had been down to less than fifty feet, molesting the treetops. For the last four days it had been going up and down every few hours. It stayed up long enough to get a trip or two in before coming back down again to ground me. I thought myself familiar enough with its pattern to stay safe, but I was wrong.

After working my way around some higher terrain that disappeared up into the cloud cover, I located the hunting camp in a small clearing by the river’s edge. I landed on the dark, rust-colored water, cut the motor and glided to shore, allowing the tips of the floats to kiss the sandy bottom near the riverbank. I walked out onto the float and stepped through the shallow, weedy water in hip waders.

The kid I was there to pick up was nowhere to be seen, but his father walked up to say hello. We shook hands, eyeing one another. Slightly taller than me, he had a rugged face and a serious look about him. He wore heavy hunting clothes against the brisk fall air.

A huge, bloody, quartered bull moose lay on a tarp with its fur still on. Its massive, severed head had a large caliber bullet hole in its nose. My eyebrows must have gone up because the man said, “Yeah, I know. My son was excited when he took the shot; it was his first time, but I’m proud of him.”

“Right, so where is he?” I asked.

“He’ll be along soon. He went to get some gear we left down-river at the kill site. He shouldn’t be too long.”

It was then that the other two hunters stranded nearby came to mind. Without thinking, I said, “Okay then, I’ll be right back.”

I took off again and headed for the other camp, but soon had to turn back where the cloud cover met the rising terrain. I landed on the river again. It gave me an uneasy feeling to have used up that fuel.

The cloud cover soon slipped back down close to the trees again. That it changed so quickly should have told me something.

The kid was there now, his pile of gear by his kill. We shook hands and exchanged greetings. I made him out to be about eighteen years old, with a slight build and dark hair pushed back on his scalp. He had clear, intelligent eyes.

His father, who would be staying there longer, took me aside and said, “Listen, I really don’t like this weather. Why don’t you camp here with us tonight and make the trip in the morning? We have enough food and an extra sleeping bag. I also have a bottle of whiskey if that’ll sway you.”

His eyes were full of hope that I’d say yes. I looked up at the ceiling again as though considering his offer, but I was really thinking about sleeping in my own bed that night instead of on the cold, hard ground by that river.

“No, it‘ll be okay,” I said. “It’s been doing this for days, but it’s fairly predictable and I’m used to it, so no sweat. Let’s get the plane loaded and wait for it to lift again, which I know it will.”

He looked at me seriously for a few seconds, measuring my words against what he saw in my face. It was my decision to make, so he turned and busied himself around the campfire.

The fog was just off the treetops as we loaded the kid’s duffle bag, his rifle and some other gear into the back of the plane. Then I cross-spooned the heavy moose quarters in to save space. After that we each grabbed an end of the big antlers and worked the colossal head in, facing forward toward the cockpit. Its dead eyes stared dully from behind the gaping bullet hole in its nose, an image I knew would be with me longer than I cared to think about.

Once we had the plane loaded, the three of us sat around the fire drinking coffee, waiting to see what the fog would do. We didn’t say too much. The kid seemed happy about making his first kill. The father had a worried look on his face, having resigned himself to my decision to go.

It took a little over an hour for the ceiling to make its way back up to a few hundred feet. “Okay let’s go, there’s no time to waste,” I said. The father hugged his boy, then watched him climb in beside me. The boy kept looking at his father as we pulled out into the river flow. His father stared at the plane as we taxied away to lift off the river, into the killing fog.

*** To be continued ***

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Join Ray's email list and we'll let you know when the second half is posted... Sign Up Here!

Thanks to Evangeline Presents and Maple Street Music for their work to make this new project come to life.